Most of the United States was still a wide open wilderness when the Great War between the states broke out. Young men who knew little about life beyond the borders of their own farm’s fence rail were suddenly far from home and doing what was previously unthinkable.

While some boys came home with doctoring skills, others brought home the lucrative specialty title “Embalming Surgeon.” Those who were willing to abandon their post (and could stomach it) were hired away from the armies of both sides by the booming embalming service businesses.

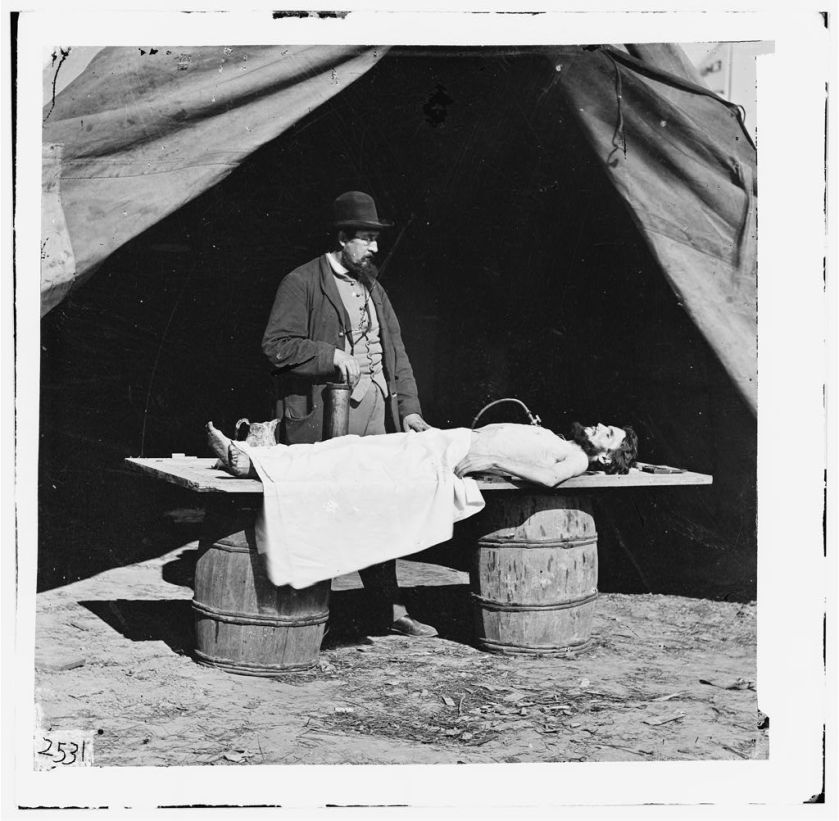

Field embalming could be completed in about two hours, with a minimal investment in chemicals. These gruesome entrepreneurs followed behind active battles with their tents and supplies. They employed men as “pickers” to glean blood soaked fields in search of freshly dead and mostly intact men.

“Runners” were used to contact the agents whose territory included the deadmen’s hometown. With such a streamlined system in place, the embalmer’s agents often delivered the grievous news before the official Army telegrams were dispatched. No time was wasted in the rush to sell devastated loved ones services for preservation and shipping of their soldier’s remains.

By railroad rules, only embalmed corpses would be accepted for transport. No spoiled (foul smelling) cargo of any kind was allowed. At the beginning of the great conflict between the states, bodies were packed and crated in straw and ice. However, as the war continued, delays and detours became common, and iced corpses could putrefy beside other cargo before reaching home.

When Pickers ran out onto a new battlefield, officers’ remains were favored over enlisted men. Their families were likely to be wealthier. With fees around $50 for an officer, and $25 for an enlisted man ($2500 and $1250 in today’s money) there were fortunes to be made. The service’s price included packing the remains in crudely made wood transport coffins lined with zinc against leakage.

Of course there were some Agents who were just plain cheats. These swindlers set a price upon seeing the dead soldier’s home; sometimes demanding outrageous fees at large homes with the threat of discarding the body; effectively ransoming the corpse to loved ones.

After President Lincoln’s body made its fourteen day farewell tour by train, the public in all parts of the country embraced the previously rare practice of routine embalming. Still, the market for Embalming Surgeons quickly evaporated. Undertakers at home were already set up with profitable furniture and coffin making shops. They had digging crews and fancied-up funeral hacks called “hearses” to tote the departed in.

For hometown undertakers, adding this service was an easy moneymaker. Some Embalming Surgeons found work with established undertakers; most turned to farming or whatever trade they’d left off with before the war.

Can’t find an old photo of an event relevant to your Family History? Check out the Library of Congress Image Collection. You can search by collection, events, or key words. In most cases, usage availability is noted. A few will suggest a search before using the image for publication or display (like on a blog or publication). Their cache of available photos and other forms of imagery is incredible–make it a part of your writing and researching toolbox!